Fundamentally, the psychological contract expresses the combination of beliefs held by an individual and his or her employer about what they expect of one another. It can be described as the set of reciprocal but unarticulated expectations that exist between individual employees and their employers. As defined by Schein (1965): ‘The notion of a psychological contract implies that there is an unwritten set of expectations operating at all times between every member of an organization and the various managers and others in that organization.’

This definition was amplified by Rousseau and Wade-Benzoni (1994) who stated that:

This definition was amplified by Rousseau and Wade-Benzoni (1994) who stated that:

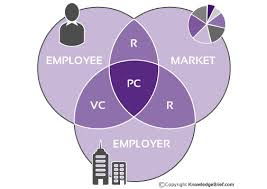

Psychological contracts refer to beliefs that individuals hold regarding promises made, accepted and relied upon between themselves and another. (In the case of organizations, these parties include an employee, client, manager, and/or organization as a whole.) Because psychological contracts represent how people interpret promises and commitments, both parties in the same employment relationship (employer and employee) can have different views regarding specific terms.

Sparrow (1999b) defined the psychological contract as:

an open-ended agreement about what the individual and the organization expect to give and receive in return from the employment relationship… psychological contracts represent a dynamic and reciprocal deal… New expectations are added over time as perceptions about the employer's commitment evolve. These unwritten individual contracts are therefore concerned with the social and emotional aspects of the exchange between employer and employee.

Within organizations, as Katz and Kahn (1966) pointed out, every role is basically a set of behavioural expectations. These expectations are often implicit – they are not defined in the employment contract. Basic models of motivation such as expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964) and operant conditioning (Skinner, 1974) maintain that employees behave in ways they expect will produce positive outcomes. But they do not necessarily know what to expect. As Rousseau and Greller (1994) comment:

The ideal contract in employment would detail expectations of both employee and employer. Typical contracts, however, are incomplete due to bounded rationality, which limits individual information seeking, and to a changing organizational environment that makes it impossible to specify all conditions up front. Both employee and employer are left to fill up the blanks.

The notion of bounded rationality expresses the belief that while people often try to act rationally, the extent to which they do so is limited by their emotional reactions to the situation they are in.

Employees may expect to be treated fairly as human beings, to be provided with work that uses their abilities, to be rewarded equitably in accordance with their contribution, to be able to display competence, to have opportunities for further growth, to know what is expected of them and to be given feedback (preferably positive) on how they are doing. Employers may expect employees to do their best on behalf of the organization – ‘to put themselves out for the company’ – to be fully committed to its values, to be compliant and loyal, and to enhance the image of the organization with its customers and suppliers. Sometimes these assumptions are justified – often they are not. Mutual misunderstandings can cause friction and stress and lead to recriminations and poor performance, or to a termination of the employment relationship.

To summarize, in the words of Guest and Conway (1998), the psychological contract lacks many of the characteristics of the formal contract: ‘It is not generally written down, it is somewhat blurred at the edges, and it cannot be enforced in a court or tribunal.’ They believe that: ‘The psychological contract is best seen as a metaphor; a word or phrase borrowed from another context which helps us make sense of our experience. The psychological contract is a way of interpreting the state of the employment relationship and helping to plot significant changes.’

No comments:

Post a Comment